The urgent need to preserve a cornerstone of American culture led folklorists like John Lomax to travel the country documenting early blues recordings and writers like Amiri Baraka to publish “Blues People: Negro Music in White America.” Although Margo Cooper did not know it when she began more than 20 years ago, she has followed that tradition and produced a documentary project that archives the oral and visual histories of blues musicians, their families and communities in northern Mississippi and the Delta.

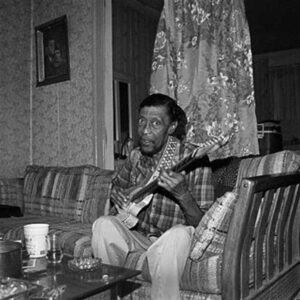

Her project, “Deep Inside the Blues,” includes B. B. King, Sam Carr, Bobby Rush, R. L. Burnside, Otha Turner and many others. It is, for her, a love letter to the people she befriended in the Deep South. It is also, for her, a love letter to the genre that entranced her when she was a teenager. What started simply as a passion for the blues in high school developed into something deeper, as she discovered love and suffering, survival and self-determination, joy and pain, a light in the darkness.

“A friend of mine played Play the Blues, an album by Junior Wells and Buddy Guy, and this song, ‘Messin’ With the Kid,’ planted a seed,” Ms. Cooper said. “I was hooked. I didn’t pursue it until years later.”

Her interest in the music grew as she went to blues clubs around New England, where she lived. That was accompanied by the realization that to really understand the music, she had to go to Mississippi. Having practiced law as a public defender for years, Ms. Cooper refined her photographic skills in the mid-1990s at the Maine Photographic Workshop, where she met the documentary photographer Jerry Berndt, who became her mentor, and Sylvia Plachy, who would help her edit and sequence the photos in “Deep Inside the Blues.”

Ms. Cooper had decided to combine her love of photography and the blues with an oral history project while working as a contributing photographer for Living Blues magazine. Before she took her first trip to the Delta in 1997, David Nelson, former editor of Living Blues, drew a map and said she should go to the Otha Turner family picnic. Othar (Otha) Turner was one of the last well-known fife and drum players, having learned to play the fife, a flutelike instrument, when he was 16. He began hosting Labor Day picnics in the late 1950s. His family gathering grew to attract blues fans from all over the world.

“Otha would slaughter the goats and they would make barbecue goat sandwiches, fish sandwiches; people from all over the community would come,” Ms. Cooper said. “He was a legend, he was funny and he was strong. I became friends with Otha and his daughter and attended the picnic for 15 or 16 years.”

Knowing that many of the musicians are in their 70s and 80s, she felt an urgency to get as many of their stories as possible. Their age also means many of them have been witnesses to history. Willie “Big Eyes’” Smith, who was a drummer for Muddy Waters, recalled the 1955 murder of Emmett TIll, who was 14 when he was killed in Mississippi.

“I went to the funeral and seen him in the coffin,” Mr. Smith said. “I’m only 18 years old. I’m mad as hell. They went to stopping cars from the North going South because everybody was mad. That was really the beginning of the civil rights movement. You’d always see signs of the K.K.K. driving down the country roads. Even in the late ’80s I saw a black doll with a rope around its neck hanging from a porch. I’d think, what kind of a mind you got to be that stupid? I never went to no back door. I would have had to do without if I had to go to the back door.”

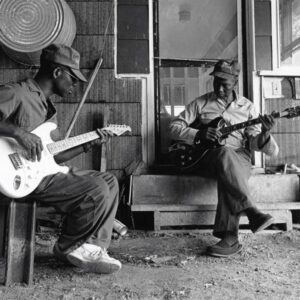

The love of the culture extends to the current generation, like Shardé Thomas, Otha Turner’s granddaughter, and Cedric Burnside, whose duo continues the tradition of his grandfather R. L. Burnside.

“He told me never to let anybody tell me that I wasn’t good enough to play the music,” Cedric Burnside said. “I’ve been to beautiful places all over the world, but I never want to live anywhere other than Mississippi. It’s beautiful to me. You have a lot of poor people who grew up in shack houses and it’s the only property they have, but they pass it on to their children. The air is pure. The land is green and I love it.”

Of course, the blues also has power to heal in places where racism and economic disenfranchisement linger.

“The blues has an outlook that asserts if you can deal with suffering and heartache, then you can handle anything,” said Charlie Braxton, a Mississippi native, music critic and author. “The music and the ideology itself will never die. And the one thing that oppression teaches you is that no one can survive alone, no one has a padlock on pain.”

Ms. Cooper can relate to that.

“My interest in storytelling and photography started with me sitting with my grandmother looking at the photo album,” she said. “As a kid, I would ask her who are those people and I would write down their stories. Certainly I know about the Holocaust and hard times, and prejudice. We know that prejudice still exists. We share a respect for our ancestors as a part of tradition.”

Fayemi Shakur is a writer based in Newark. Her work has been featured online and in print in Nueva Luz Photographic Journal, The International Review of African American Art, and Hycide Magazine.