Page 53 - Blues Festival Guide Magazine 2019

P. 53

Black musicians to congregate and socialize after gigs, it was

also a place for Black musicians to rent rooms when gigging in

town. Jelly Roll Morton lived in one of the rooms for a time.

In the South, there were designated homes that housed not

only traveling musicians, but African American workers as well.

Places like this wouldn’t be in the Green Book because they

were off the radar and in rural communities, only known by

those who traveled those roads. If you’re familiar with how the

NAACP sent representatives to different cities to monitor court

cases, then you’d also remember that they had volunteers who

allowed representatives or those facing the legal system, to stay

in their homes. Again, to ensure the safety of the volunteers, this

information wouldn’t be published in a book.

Some of the homes that rented rooms to traveling bluesmen

were known as “Hot Suppers.” These were Black institutions that

gave a form of escape to sharecroppers, allowing them to enjoy

themselves away from white people. Documentation shows

they began in the late 1800s, later to become known as liquor

efficient. This led to a new industry where African American blues

musicians traveled around the South and Midwest for gigs and

recording sessions, usually with weapons. They slept in the homes

of African Americans who rented out rooms to traveling musicians,

none which were found in the Green Book. It was shared through

word of mouth.

Michael Dolphin, the son of the legendary music mogul John

Dolphin (owner and operator of Dolphins of Hollywood on Central

Avenue in Los Angeles), shares, “During this time, bluesmen

stayed either with friends or relatives, and the promoters would

also guarantee housing because safety was always a concern.”

Traveling was troublesome, so there were kinfolk networks that

musicians were familiar with. If they didn’t know the “who” or

“where” prior to their excursion, they were given instructions

on who to look for and where to find them upon arrival. The

kinfolk community system has been a major part of the African

American community since slavery, abolition and the underground

railroad. Considering that the majority of the country blues artists

traveling during this time either started on a plantation or were

sharecroppers, this system wasn’t foreign to them.

In 1904, the New Amsterdam Musical Association, which

was the first African American musician’s union in America, was

established. Now operating as a nonprofit with landmark status,

the organization has been a staple for the African American

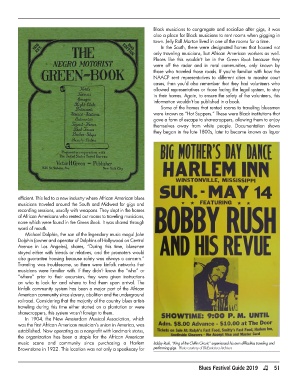

music scene and community since purchasing a Harlem Bobby Rush, “King of the Chitlin Circuit,” experienced his own difficulties traveling and

Brownstone in 1922. This location was not only a speakeasy for performing gigs. Photo courtesy of BluEsoterica Archives

Blues Festival Guide 2019 51