Page 75 - Blues Festival Guide Magazine 2018

P. 75

and Charlie McCoy, sometimes by way of St. Louis, Memphis,

Indianapolis or other cities.

By 1930, Chicago had more Mississippi-born black residents

(38,356 by census figures) than any other city in the country,

and twice as many as Jackson, Mississippi’s largest city. St. Louis

had a smaller population but an even higher percentage of

Mississippians and was, at one point, America’s most important

center for blues activity, making it an appropriate city to house

the National Blues Museum.

The steady stream of migration to Chicago and other cities

of industry grew into a torrent during the 1940s and ‘50s fueled

by political and technological changes. As the nation geared

up for another war, factories, processing plants and steel mills

needed new masses of workers, prompting the largest exodus

from the South. Labor was still needed in the South to produce

cotton, exempting Muddy Waters, B.B. King and certain other

valued plantation residents from service, but new machinery

began to replace the field hands. At the same time, as black

soldiers returned home from war, the demand for equal rights

and better pay grew. Leaving home was the obvious response

for many. Between 1940 and 1950, an estimated 150,000

African Americans left Mississippi for Chicago.

The new wave of migrants transformed the sound of Chicago

blues, led by Muddy Waters and his band, and promoted by

a new cadre of independent record labels like Chess and Vee-

Jay. While blues was already established in the city, much of it

had developed a smooth, urbane veneer, and many Chicago

sophisticates looked askance at the downhome variety of blues.

The recordings of the ‘30s and early ‘40s often evidenced this,

and the live entertainment that Chicago’s black newspaper, The

Defender, preferred to promote was either lighter fare or more

jazz-oriented. The transplantation of raw, hard-edged blues

from the Delta and other regions of the Deep South by Muddy,

Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter, Jimmy Reed, Elmore James, Sonny

Boy Williamson II, Jimmy Rogers, Snooky Pryor, Junior Wells and

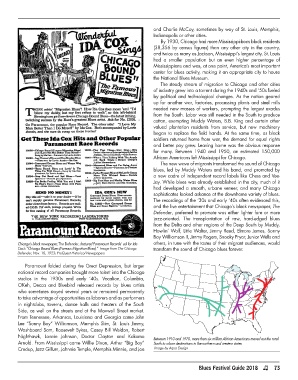

Chicago’s black newspaper, The Defender, featured Paramount Records’ ad for Ida others, in tune with the tastes of their migrant audiences, would

Cox’s “Chicago Bound Blues (Famous Migration Blues).” Image from The Chicago transform the sound of Chicago blues forever.

Defender, Nov. 10, 1923; ProQuest Historical Newspapers

Paramount folded during the Great Depression, but larger

national record companies brought more talent into the Chicago

studios in the 1930s and early ‘40s. Vocalion, Columbia,

OKeh, Decca and Bluebird released records by blues artists

who sometimes stayed several years or remained permanently

to take advantage of opportunities as laborers and as performers

in nightclubs, taverns, dance halls and theaters of the South

Side, as well on the streets and at the Maxwell Street market.

From Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana and Georgia came John

Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson, Memphis Slim, St. Louis Jimmy,

Washboard Sam, Roosevelt Sykes, Casey Bill Weldon, Robert

Nighthawk, Lonnie Johnson, Doctor Clayton and Kokomo Between 1910 and 1970, more than six million African Americans moved out the rural

Arnold. From Mississippi came Willie Dixon, Arthur “Big Boy” South to urban destinations in the northern and western states

Crudup, Jazz Gillum, Johnnie Temple, Memphis Minnie, and Joe Image by Aqua Design

Blues Festival Guide 2018 73